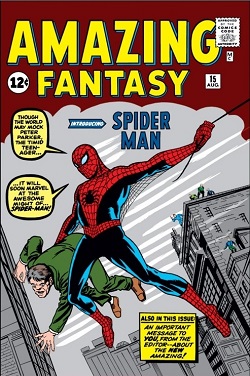

| Spider-Man debuts: Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and Steve Ditko (inker). (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

What Marvel Comics used to call "the dreaded deadline doom" is upon me. It's Saturday, and I don't have a new topic to write about. Here's a favorite from 2009. This article originally appeared on Suite 101.

Use dramatic structure to keep your readers hanging—not yourself!

Losing control of the story is one of the worst things that can happen to a writer in any genre, but it is especially perilous for comic book writers who depend on exciting and often super-heroic tales to keep readers coming back month after month, year after year.

But sooner or later, readers tire of stories that never end. Developments meant to hold readers’ interest can often backfire if they seem too far-fetched or appear “out of the blue.” One reason why writers resort to such tricks is because they haven’t thought out the story’s structure.

Freytag's Pyramid

Dramatic structure is a fairly simple device to keep the writer on track, regardless of story length. Structure requires the writer to know the beginning, middle, and end of her story, and to recoognize when she has reached each point.

| Freytag's pyramid (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

While there are many ways of looking at story structure, one of the most useful patterns is Freytag’s Pyramid. Named after Gustav Freytag, the 19th century novelist and dramatist who devised it, Freytag’s Pyramid divides the elements of a story into five (sometimes seven) categories and identifies the function of each element.

Many graphic representations and explanations of the pyramid can be found online, but to illustrate its usefulness in writing comic books, let’s look at one of the most popular comic book stories of all time.

Many graphic representations and explanations of the pyramid can be found online, but to illustrate its usefulness in writing comic books, let’s look at one of the most popular comic book stories of all time.

Spoiler Warning: This section analyzes the origin of Spider-Man. If you are not familiar with the origin and don’t want to know how it ends, proceed at your own risk.

Originally published in Amazing Fantasy # 15, August 1962, the origin of Spider-Man has been told and retold countless times. Some details have been embellished, added, and altered in subsequent comics and even films, but notice how the underlying structure developed by writer Stan Lee and artist Steve Ditko remains intact:

- Exposition (What information does the reader need to know in order to understand the story?)

Peter Parker, science nerd, is shy around girls, picked on by jocks, and doted on by Aunt May and Uncle Ben.

- Inciting Incident (What happens to disrupt the character's normal life?)

Peter is bitten by a radioactive spider.

- Rising Action (Things either start going well for the hero or poorly, depending on the type of story you are telling.)

Peter discovers that he has powers and creates his Spider-Man costume. He tries to cash in on his abilities by wrestling.

- Climax (This is often a moment of truth, a moment when our hero’s fortunes change.)

Peter refuses to stop a burglar.

- Falling Action (The reversal of Rising Action; if things were going well before, they go poorly now, or vice versa.)

Returning home, Peter learns that Uncle Ben has been killed by an intruder. As Spider-Man, Peter tracks the killer to a warehouse and fights him.

- Resolution (How does the story end?)

- Denouement (What is the outcome of the story?)

Peter learns that “with great power comes great responsibility” and vows to use his powers to help others.

Not every story will fit into the pattern as neatly as Spider-Man’s origin, and there is room for some interpretation. (Does the true climax occur when Spidey confronts the burglar?) But the pattern itself gives the story power and meaning. It tells us when the story ends and why it is significant.

Without a solid structure, Spidey could be chasing the burglar through a 12-issue maxi-series with numerous crossovers by way of the Avengers and never get a resolution. Or if the resolution does come, it might be delayed for so long that the readers who have stuck with you have forgotten its significance.

Try plotting your own story on Freytag’s Pyramid. Use one or two sentence descriptions to identify the most important actions that take place in each category. Look for a strong climax and resolution. Then add subplots, cross-overs, and other frills as needed.

Source:

Lee, Stan, writer, and Steve Ditko, artist. “Spider-Man!” Amazing Fantasy 15 (Aug. 1962).

2 comments:

Freytag's Pyramid is what I call "encounter, conflict, resolution", and to me is the key to any story, chapter, or scene. To move the story forward every scene must have something in it that deepens the plot, casts the characters further into danger or intrigue, and deepen their predicament. Only then can the "resolution" part begin, leading to the climax and ending of the story.

And by the way, when I was in high school, working at a drugstore that handled comics, I owned that book, not to mention FF 1, Spiderman 1, and a host of other Marvel classics. Wish I had them now!

I wasn't even born when Amazing Fantasy # 15 hit the stands--but I did get later reprints.

Post a Comment