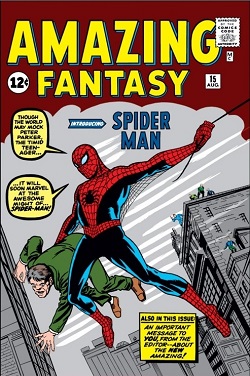

Spider-Man debuts: Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and Steve Ditko (inker). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Spider-Man debuts: Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and Steve Ditko (inker). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)If you're writing a story that features a young hero, one of the most difficult questions you will have to answer is this: How many parents should your character have? Two? One? None?

Why is this difficult? Because writers often pattern their young characters after themselves at the same age, and killing off your character’s parents can feel like killing off your own.

Also, doing away with your character’s parents flies in the face of our normal human desire for our characters to be happy, healthy, and whole.

Yet heroes who have lost one or both parents dominate all kinds of fiction: Superman, Spider-Man, Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games, Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird, and so forth. “Cinderella,” “Hansel and Gretel,” and other children's stories also feature heroes whose parents are either dead or absent.

Why can offing your character's parents be a good thing? Let's take a closer look at some of the examples above:

Katniss Everdeen

Katniss lost her father to a mining accident some years before The Hunger Games begins, leaving her to care for her emotionally absent mother and very young sister. Although it’s not explicitly stated in the film, Katniss appears to be her family’s sole provider: she hunts and begs for food.

These dire circumstances imbue Katniss with a streak of independence and strength of character which make her actions in the story plausible. Protective of her sister, Katniss volunteers to take her place in the Hunger Games. Able to hunt and hide, she possesses an advantage over most of her competitors.

In short, the loss of her father has turned Katniss into a survivor.

Scout Finch

Jean Louise “Scout” Finch ages from six to eight in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, but Scout lost her mother when she was two. Although she and her older brother, Jem, are looked after by their father’s cook, Calpurnia, the absence of a close female role model becomes apparent when Scout’s aunt, Alexandra, comes to live with them.

Alexandra tries to mold Scout into a lady and indoctrinate her into the beliefs and practices considered proper for ladies in their small, 1930s Alabama town. But tomboy Scout wears overalls, gets into fights with Jem and other boys, and sneaks into the courthouse to watch her father, lawyer Atticus Finch, at work.

In fact, Scout’s close relationship with her father plays a significant role in her open-mindedness and acceptance of people who are different from her (such as black people and the Finch's reclusive neighbor, Boo Radley), attitudes which are decidedly at odds with the judgmental and racist views common in her town. Scout learns to see the world through another's perspective, echoing her father's philosophy.

Had her mother lived, the novel implies, Scout may not have had such a close relationship with Atticus.

Superman and Spider-Man

Both are orphans. Superman lost not only his natural parents but his entire world when Krypton exploded. Raised by the kindly Kents, he becomes orphaned a second time when they pass away (in the original continuity, at least).

Why was it necessary for Superman to lose two sets of parent? The answer DC Comics gave was to show that, for all his powers, Superman was not a god. There were things he could not control, such as death.

Spider-Man’s parents died when he was young, and he was raised by his aunt and uncle. He, too, experiences a second tragedy when Uncle Ben is shot and killed, which provides Spider-Man with his motivation to become a hero: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Would it have made a difference if Ben Parker were Spidey’s father instead of his uncle? Perhaps writer Stan Lee chose to distance Peter Parker from his natural parents because the death of a parent in story would have been too schocking or hard for his young readers to take. (Consider how the murder of Batman’s parents, which happens in story, makes that character so much darker and his readers’ expectations of him so different from the examples above.)

Katniss, Scout, Superman and Spidey lost one or both parents years before each of their stories begins. In each case (except Katniss), they are too young to remember the lost parent or parents. This allows the reader to feel sympathy toward them without being too horrified or grief-stricken.

Damon and The Power Club

Truth is, it never occurred to me to kill them off before. Even now, I'm on the fence about doing so. Damon has plenty of other things to cause him consternation, and I want him to be an individual character, not an archetype.

Besides, some stories do feature heroes whose parents live. (The Waltons and numerous other TV series come to mind.)

Another besides: Damon’s entire story has yet to be be written, so who knows what the future holds in store for Mr. and Mrs. Neumeyer?

Tie Your Mother Down?

So, why should you consider offing your character's parents? Because in our world the traditional family unit of two parents and 2.5 children is, whether we admit it or not, often considered the norm—the ideal standard for raising healthy, happy, and whole children. At least that's what many of our politicians say.

But your hero lives in an imperfect world (as do most of your readers). Something is missing and your hero sets out on a quest to find it. Or something is not right, and your hero tries to fix it.

Taking your hero out of her "perfect" world sets your story in motion.

If you like this post, you may also like:

Playing the Game: How The Hunger Games Combines Adventure and Social Commentary

Should Writers Be Original or Do What the “Experts” Say?

- Superman Vs. Batman: Choose Your Icon