“Damon, wake up,” his mother said softly. “It’s Christmas.”

His eyes shot open. The morning glare hit him like a brass band.

“Take it easy,” his mother said. “Let’s see if you’re up to finding out what Santa brought you. Oh, I’m sorry. I forgot.”

Damon didn’t realize at first why she was apologizing. He looked around the room, trying to remember . . . what?

“Mom? Did someone come into our house last night?”

“Don’t tell me you’re going back to believing in Santa Claus, dear,” she said as he felt his forehead. “Good news: Your fever broke. Why don’t you go see what you got for Christmas?”

Damon sat up. He felt . . . strange, as if part of his brain were still asleep. He remembered exhaling and summoning the darkspace, but he couldn’t remember making it go away – and Damon always remembered that! He also remembered . . .

The door handle!

He ran to the front door. It looked undisturbed. He reached for the handle to see if it was locked.

“Why are you going outside?” his mother called to him. “Go to the Christmas tree and see what presents you have.”

The tree was surrounded by red and green packages with pictures of Santa, bells or angels. There were a few gifts from Grandma and Grandpa Neumeyer, who always used the same white and blue-striped wrapping year after year.

Eldon was already unwrapping a toy bulldozer. He looked up when he saw Damon. “Did you see him? Did you see Santa?”

Damon hesitated. “I don’t know.”

Eldon frowned. “I knew you couldn’t stay awake all night.”

“But I did! At least I think I did.” Damon felt disappointed. He must have fallen asleep, after all, and dreamed the whole thing.

Eldon smiled mysteriously. “Well, you musta’ seen somebody.”

“What do you mean?”

“You got an extra present.”

Damon looked at the gifts under the tree, and there it was: a present in sky-blue paper, no bigger than a shoebox. His name was written across the paper in a handwriting he didn’t recognize. He picked up the gift, tore off the paper, and gasped.

It was a Captain Meteor action figure.

Damon opened the attached card. In the same handwriting, it read:

Dear Damon,

You won’t remember what happened last night because I used fairy dust to make you forget. But you did something extraordinary – so Santa’s going to let you in on his little secret.

When I opened your front door, it was black as a pit in your house! Now, I’m used to coming to the district and all the powers some of you kids have, but my new elf assistant, Seymour, wasn’t. He panicked, ran outside, and slipped on the ice. He hurt his leg badly. Luckily, adults don’t believe in Santa or elves anymore, so your parents weren't awakened by his howling.

Well, you felt so bad about what happened that you came outside, sick as you were, and tried to help. You told Seymour stories about Capt. Meteor to get his mind off the pain while Santa used another batch of fairy dust to make him better.

I’m so touched by what you did (but not Seymour – who says he’s never coming back to the district again!) that I want you to have your own Capt. Meteor. Your mother’s right – he’s very expensive, so take good care of him. More imporantly, you’ve got an amazing power. Use it wisely, like Capt. Meteor would.

Santa

Damon searched his memory to see if any of it was true, but he couldn’t remember a thing! He ran to the window to see if there were footprints in the snow, but his dad was shoveling snow off the sidewalk.

“No!” Damon shouted.

“What’s the matter?” Eldon asked.

Damon thrust the card to his brother, but Eldon missed it. The card fluttered to the floor. When Eldon picked it up, he looked puzzled and showed it to Damon. The card was blank.

Eldon laughed when Damon told him what the card had said. “It didn’t say that! You made it up!”

“It’s true! Didn’t Seymour’s howling wake you up last night?”

Eldon looked down at the bulldozer. “I was already awake. I was watching for Santa through the upstairs window when I saw a Hummer park across the street and two people got out.”

Damon nodded, remembering that he’d seen the Hummer, too. “It was just the district police, making their rounds.”

Eldon shook his head. “It wasn’t the police. It was just people who work for the district. They went to one house after another, carrying presents.”

Damon studied the Captain Meteor action figure. “But why would people from the district bring us presents?”

“Don’t they teach you anything in that special school you go to?” Eldon said, rolling his eyes. “The district wants us to have a normal life, so they give us stuff ‘cause there aren’t many places inside the district to buy toys.”

“You saw them come into our house?” Damon said, bewildered.

“’course not!” Eldon replied, reminding Damon that, from their room, they couldn’t see the front porch. “But who else could ita’ been?” He walked back to his new bulldozer. “Last year, they drove a Chevrolet. I guessed the district was too dangerous for Santa to drive a sleigh, but, when I saw that Hummer, I stopped believing in Santa Claus.”

Damon felt like a balloon that had lost its helium. It all made sense. Workers from the district would have keys to all the houses. And maybe one of the workers had a power to make Damon forget. They could have used a disappearing ink on the card.

He held the action figure away from himself, as if it were an unwanted thing. Through the packaging, Captain Meteor’s painted-on eyes stared at him with confidence and power as if to echo what the card had said.

You’ve got an amazing power. Use it wisely.

Damon decided it didn’t matter if Santa Claus was real or not. He carefully opened the package and took out his new toy.

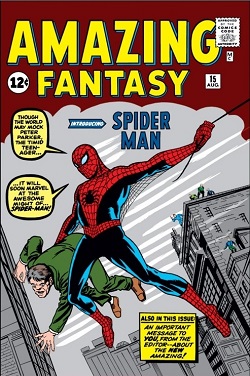

Spider-Man debuts: Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and Steve Ditko (inker). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Spider-Man debuts: Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962). Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and Steve Ditko (inker). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)