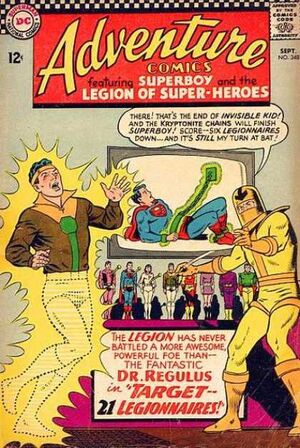

Last week, we talked about the pratfalls of forcing your

characters to serve the needs of the plot. I used a classic Legion of Super-Heroes story from Adventure Comics to demonstrate how writers can unintentionally make their characters act like puppets in order to do what the plot requires them to do.

This time, we’ll look at a different Adventure story to illustrate how plot should flow from the

characters instead of the other way around. This story gets the balance between character and plot just right.

“The Legionnaire Who Killed” (Adventure Comics # 342, March 1966)

Spoiler warning: The rest of this post discusses plot elements of the story in question. Read at your own risk.

Arguably one of the most famous Legion stories of all time, “The Legionnaire Who Killed” had lasting repercussions for the titular characters for decades to come. It is also one of the last Legion stories written by Edmond Hamilton, a noted science fiction author who had been one of the Legion’s two regular writers (the other being Jerry Siegel) during its formative years.

Arguably one of the most famous Legion stories of all time, “The Legionnaire Who Killed” had lasting repercussions for the titular characters for decades to come. It is also one of the last Legion stories written by Edmond Hamilton, a noted science fiction author who had been one of the Legion’s two regular writers (the other being Jerry Siegel) during its formative years.

|

| Copr. and TM DC Comics Inc. |

In “The Legionnaire Who Killed,” however, Hamilton crafts a

story that honors his characters as individuals, respects the difficult

situation they find themselves in, and trusts the readers to embrace an ending

that does not turn out the way we hope.

The story centers on Star Boy (Thom Kallor), a Legionnaire

known for his purple and white costume, crew cut, and power to make objects

super-heavy.

Feeling lonely because the girl he likes, one-time Legionnaire Dream Girl, is far away, Star Boy takes a leave of absence to visit his parents on a distant jungle world. Arriving just after they’ve left, Star Boy is confronted by Kenz Nuhor, a baddie whose advances Dream Girl has spurned because she’s in love with Star Boy. Like a typical psychopath, Nuhor decides the way to win Dream Girl’s heart is to kill his rival.

Feeling lonely because the girl he likes, one-time Legionnaire Dream Girl, is far away, Star Boy takes a leave of absence to visit his parents on a distant jungle world. Arriving just after they’ve left, Star Boy is confronted by Kenz Nuhor, a baddie whose advances Dream Girl has spurned because she’s in love with Star Boy. Like a typical psychopath, Nuhor decides the way to win Dream Girl’s heart is to kill his rival.

Star Boy, his power useless against Nuhor’s special shield, does what

any clear-thinking individual would do under the circumstances: He picks up a

gun dropped by a hunter Nuhor has killed and shoots the villain dead.

The problem? Killing is

against the Legion’s code.

Thom's Legion buddies haul his butt before a court martial. During the trial, several

significant issues are raised: Did Star Boy break the Legion’s code even though

he acted in self defense? Could he have

stopped Nuhor without killing him? Should Legionnaires have the right to kill in self defense?

While the Legionnaires grapple with these issues and Thom’s

fate, they behave in manners which are wholly appropriate to their characters. Their actions, in turn, drive the plot:

- Brainiac 5, serving as prosecutor, “proves” that Thom could have disabled Nuhor by making a thick tree limb above Nuhor’s head heavy enough to fall on top of the villain. (Never mind that doing so might have broken the villain’s neck, leaving Star Boy in the same fix he’s in. The prosecutor’s role is only to create an element of doubt, and Brainy—cold and composed—does so in a manner that would make Jack McCoy proud.) Brainiac 5 serves as the story’s antagonist by continually thwarting the hero’s desire (to be acquitted).

- Superboy, serving as defense attorney, goes to great and sometimes questionable lengths to get his client off. He stages a mock attack with a dangerous beast to trick other Legionnaires into trying to kill the beast. He turns the tables on Brainiac 5 by accusing the latter of having previously killed a foe. Superboy’s efforts fail because, in both cases, he has not done enough research. However, his failures keep the plot moving forward and heighten the tension.

- Star Boy, once the trial begins, can do nothing but sit tight in the Legion’s holding cell and express his faith in Superboy’s defense. But even here Star Boy remains our protagonist—the one we care about and sympathize with. We know he “broke the law,” even though we understand why he did so, and we want him to win even though we know there must be consequences for his actions.

- Dream Girl is more than a love interest here. Although she starts the story as a MacGuffin, she plays a crucial role in supporting Star Boy and adding tension when the latter suspects her ability to predict the future has foretold that he will lose the case. (In a brilliant bit of story telling, we’re never told if she has foreseen the outcome of the trial or not; this is left to our interpretation.) Dream Girl also plays a significant role in the ending by turning the tragic outcome of the trial into a positive for Star Boy: she convinces the Legion of Substitute-Heroes to take them both on as members.

The main characters’ actions spring logically from

the situations they find themselves in. Their reactions, in turn, drive the plot and bring it to a satisfying

conclusion.

The lessons for us as writers are four fold:

1. Know your characters well enough to anticipate how they will

react in any given situation.

We care about Star Boy because Hamilton spends some time

letting us get to know him. He misses

his girl. He wants to visit his

parents. He finds himself in an impossible

situation and must act. Star Boy comes off as Joe Average, someone anyone can identify with.

2. Let your

characters’ actions and reactions drive the needs of the plot.

If you’ve done No. 1 well, No. 2 will almost write

itself. Your characters will be strong

and proactive but also human. Their

human weaknesses will keep the plot moving forward. (If Star Boy hadn’t overlooked the tree limb,

there might be no story. If Superboy had

done his research, the trial would be over too quickly.)

3. Give your characters reasonable but competing goals.

Though he’s the antagonist, Brainiac 5 is not the

villain. He wants what every Legionnaire

wants—what’s best for the Legion. But

his goal is to uphold the Legion’s code as it exists—this means Star Boy has to go. Star Boy’s goal, obviously, is to be

exonerated and stay with the Legion. Their competing goals create the story’s conflict.

4. Let your story

resolve itself into its inevitable conclusion.

This can be a tough one because sometimes the ending we want

to write (or the ending the audience expects) isn’t what the story needs. It was risky for Hamilton to expel a Legionnaire—particularly

one he’s spent so much time making us care about—but that’s what makes this

story memorable. If Star Boy had been

acquitted, it would have been business as usual.

A story should never be business as usual.

Letting your characters control the plot instead of the other way around keeps them from acting like puppets. More, readers might just remember your story for years and even decades to come.