The following post is modified from a paper I wrote for a graduate-level course in business management. I'm posting it because it is directly relevant to the business of writing.

If the world were a perfect place, entrepreneurs could

take their wonderful ideas, turn them over to honest business professionals,

and reap huge profits while pursuing the work they love. However, the world is

not a perfect place, and business professionals are not always honest. Even ethical

arrangements among honest parties sometimes fall short of expectations due to

improper planning and lack of funding. As Schermerhorn (2013) points out,

businesses go through three life-cycle stages—birth, breakthrough, and

maturity; each stage generates its own challenges which can undermine chances

for success. Having an initial business plan, being able to locate sources of

funding, and establishing both short-term and long-term plans can help new

companies stay on track; more, they can ensure the entrepreneur keeps her most

valuable asset: control.

What the Heck Is a Business Plan, Anyway?

A business plan is defined by Schermerhorn (2013) as a

document which describes the direction and financing of a new business. For some

creative people—and what entrepreneur isn’t creative?—writing such a document

can be akin to giving birth to Rosemary’s baby. However, if entrepreneurs want

to avoid their companies turning into a devilish offspring over which they have

little or no control, such as the namesake in the 1968 horror film, Rosemary’s Baby, a business plan can

make sure there are no unexpected surprises. Drafting a business plan helps

entrepreneurs study the market for their products, determine the sort of

products and services the company will sell, and even forecast the types of

employees needed to run the company (Schermerhorn, 2013).

Business plans do not even have to be formally written

down, unless one seeks funding from banks or other lending institutions. David

Riordan, owner of OOP! an arts and crafts supply store in Providence, RI, said

he formally creates only a budget while he and his wife discuss everything else

(“Do You Have,” 2003). Even so, a business plan can be very specific in

defining goals such as numbers of transactions, volume of business, and expected

income (Huseman, 2014). With such clear goals in mind, entrepreneurs can know

what they expect the business to accomplish and anticipate how hard they will

have to work to meet those goals.

Depending on the business, entrepreneurs might need to

precede writing a business plan by conducting a feasibility study. Such a study

helps the entrepreneur decide if a project is even worth pursuing (Hofstrand

& Holz-Clause, 2013). It can also

help entrepreneurs narrow the focus of the business, understand how to position

their products, and gauge the risks involved in starting the business

(Hofstrand & Holz-Clause, 2013). There is no point in proceeding with a

business plan if no market for the product or adequate sources of financing can

be found.

Financing--How to Get Money for Your Project

Financing is a major part of setting up and running a

business. Schermerhorn (2013) lists several sources of financing available to

entrepreneurs, such as debt and equity financing, venture capitalists, and

crowd funding. The last of these, popularized by Internet firms such as

Kickstarter, Inc., enables entrepreneurs to raise money by offering “backers” free

goods and services in lieu of equity. One author, for example, has rewarded her

backers who contribute small sums of money with downloadable “Epub” copies of

her book and a mention of support on her website (Ellyn, 2012). Such

arrangements have several advantages. They are relatively easy to set up. They

can encourage many people to contribute small amounts of money for no other

reward than “warm fuzzies” (“Feel-Good Crowd Funding,” 2014). They also help

entrepreneurs raise money without having to go into debt or give up equity in

their companies (“Feel-Good Crowd Funding,” 2014).

Long- and short-term plans must also be considered by

entrepreneurs. As with the initial start-up business plan, it may seem

counterintuitive to guess where the business may be in one, five, or ten years;

however, such a plan, if flexible, can be an asset to entrepreneurs. Thompson

Lange, owner of Landscapes Carmel, a furniture store in California, had a

three-year plan for his business to earn $1.5 million; however, he anticipated

that a sluggish market might push that goal back to five years (“Do You Have,”

2003). Lange also envisioned having a second store as part of his five-year

plan (“Do You Have,” 2003). Another entrepreneur, Patti Renner, used her

long-range plans as a “learning tool” and enjoyed adjusting it to help her general

merchandise business grow (“Do You Have,” 2003).

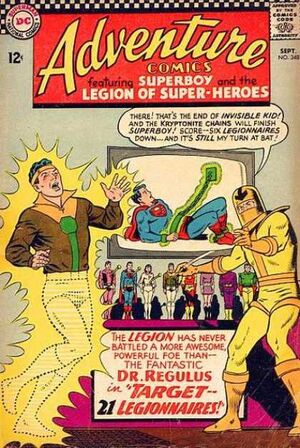

Don't Shoot Me--I'm Just the Comic Book Writer

Whatever business an entrepreneur seeks to establish—sole

proprietorship, partnership, corporation, or LLC—one of the main concerns is

control. A vivid example of what not to do can be found in the story of James

Shooter, former editor-in-chief (1978-87) of Marvel Comics. Shooter went on to

launch Voyager Communications, Inc., with two partners in 1989 (Berman, 1993).

By the early 1990s, Voyager’s Valiant imprint had successfully launched several

new comic book titles. But when conflicts of interest rose—in the forms of

dating, marriage, and nepotism—Shooter found himself outvoted and ultimately

ousted from the company into which he had poured his creative energies (Berman,

1993).

Shooter likely had all of these things—a business plan,

financing, and short- and long-term goals; his two partners, after all, were an

entertainment lawyer and a veteran publisher, while Shooter himself had been

involved in the comics industry as a writer and editor since the age of 13

(Berman, 1993). However, such experience

did not prevent one of the partners from dating a partner in the venture

capitalist firm backing the company. Shooter later allowed that he should have

walked away at that point; instead, he guided the company until it started to

turn a profit—at which point he was forced out by his remaining partner’s new brother-in-law

(Berman, 1993). Voyager became a successful company, but it did no good for the

creative entrepreneur who launched it.

No Guarantees--But Plan Ahead Anyway

The lesson from Shooter’s story is that even if an

entrepreneur does everything right, things can still go wrong. However, proper planning

can minimize the chances of entrepreneurs losing control of the company or at

least be aware of “red flags” which signal a shift away from the company’s

business and ethical goals. Writing a business plan, exploring suitable

financing options, and establishing long- and short-term goals can help

entrepreneurs retain control of their enterprises.

References

Berman.

P. (1993, June 21). How not to start a company. Forbes, 151 (13), 54-55. Retrieved from Business Source Complete database.

Do

you have a long-term business plan? (2003, December). Gifts & Decorative Accessories, 104 (12), 328. Retrieved from Business Source Complete database.

Ellyn,

R. (2012). Hot flashes of life. Kickstarter.

Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1886729316/hot-flashes-of-life/posts

Feel-good

crowd funding (2014, February). Kiplinger’s

Personal Finance, 68 (2), 26. Retrieved from Business Source Complete database.

Hofstrand,

D., & Holtz-Clause, M. (2013). What is a feasibility study? Iowa State University. Retrieved from http://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/wholefarm/html/c5-65.html

Huseman,

J. (2014, September). Origination News,

23 (11), 1. Retrieved from Business

Source Complete database.

Schermerhorn,

J.S., Jr. (2013). Management (12th

ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.