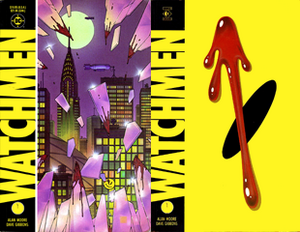

| Cover art for the 1987 U.S. (right) and U.K. (left) collected editions of Watchmen, published by DC Comics and Titan Books (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The ol' deadline doom is upon me once again. Here's a favorite article from 2009:

The first part of "Comics and Story Structure" discussed how Freytag’s Pyramid of dramatic structure can be an invaluable tool in plotting stories. To recap, the seven elements of the pyramid are:

“That’s fine,” you may say, “but what if my comic book story is a limited series or features a protagonist who isn't a cuddly, wall-crawling do-gooder?”

Structure is just as important for any type of story. The fact that some comics run for awhile on random plot lines and shock appeal does not invalidate the need for structure. Such comics sputter to a halt after awhile or degenerate into a neverending series of "character arcs" that lack any real development. Comics that operate this way usually get cancelled or relaunched, or a new writer comes in to “fix” it—often by starting a new story that lacks structure.

Structure, Stories, and Real Life

Why is structure so important? The answer can be found in Thomas Pope’s book, Good Scripts, Bad Scripts: Learning the Craft of Screenwriting Through 25 of the Best and Worst Films in History. Though written for screenwriters, Pope’s work is essential to comic book writers, as well. In his introduction, Pope reflects,"[L]ife is just one damned thing after another, without apparent structure or meaning. ... Art doesn't try to imitate life, but rather distills its essence to find and reveal the truth behind the lies, the meaning behind the meaningless, the structure within the randomness" (xix).

But what if you as a writer want to emphasize that life is, in fact, “one damned thing after another,” without meaning or structure? Many writers attempt to portray what they see as the world outside their windows, with all the grim, gritty, and amoral aspects (which might prompt one to suggest that they move to a nicer neighborhood).

Even if your story focuses on the darker side of heroes, structure can keep it from spinning out of control or sputtering to a halt eight issues into a 12-issue limited series. To illustrate this point, look at the granddaddy of all “dark” super-hero comics, Watchmen.

Watchmen and Dramatic Structure

Spoiler Warning: Aspects of Watchmen are discussed below. Proceed at your own risk.

Published as a 12-issue limited series in 1986-87 and later collected into a graphic novel, Watchmen set the tone for today's grim and gritty comics. But while many fledgling writers imitated the raw violence, sex, and language of Watchmen, they failed to learn a far more valuable lesson: Watchmen makes superb use of dramatic structure.

Writer Alan Moore put his own spin on Freytag’s Pyramid. For example, the story begins with the grisly aftermath of a murder—the “hero” known as The Comedian has been thrown through a penthouse window and his blood is being washed from the sidewalk below into the gutter. The Inciting Incident—the murder—has already occurred; this means that the opening scene begins the Rising Action. (Note that the 2009 film version departs from this beginning by showing the murder at the onset.)

But what about Exposition? Moore did not neglect this vital information. Some of it is filled in by the two detectives investigating the case; other information is discovered by another “hero,” Rorschach, as he conducts his own illegal investigation. By Page 8 of the first issue, we’re well oriented to the world of Watchmen and two of its main characters. Moore successfully weaves Exposition with Rising Action while showing us only glimpses of the Inciting Incident in flashback.

Packing and Unpacking Stories

A story, as Watchmen demonstrates, does not have to begin with Exposition. The writer can start the story anywhere along Freytag’s Pyramid. However, all of the dramatic elements should be present when the story is unpacked and laid out. (If you are familiar with Watchmen, unpack the rest of it yourself and see if you can locate the other elements.)

Good writers should also unpack their own stories and see where the dramatic beats lie. This will help you avoid “lumps” or flatness in the final product, regardless of whether it lasts one issue, 12 issues, or indefinitely.

Sources:

Moore, Alan, writer, and Dave Gibbons, artist. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics, 1986.

Pope, Thomas. Good Scripts, Bad Scripts: Learning the Craft of Screenwriting Through 25 of the Best and Worst Films in History. New York: Three Rivers, 1998.

The first part of "Comics and Story Structure" discussed how Freytag’s Pyramid of dramatic structure can be an invaluable tool in plotting stories. To recap, the seven elements of the pyramid are:

- Exposition

- Inciting Incident

- Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Resolution

- Denouement

“That’s fine,” you may say, “but what if my comic book story is a limited series or features a protagonist who isn't a cuddly, wall-crawling do-gooder?”

Structure is just as important for any type of story. The fact that some comics run for awhile on random plot lines and shock appeal does not invalidate the need for structure. Such comics sputter to a halt after awhile or degenerate into a neverending series of "character arcs" that lack any real development. Comics that operate this way usually get cancelled or relaunched, or a new writer comes in to “fix” it—often by starting a new story that lacks structure.

Structure, Stories, and Real Life

Why is structure so important? The answer can be found in Thomas Pope’s book, Good Scripts, Bad Scripts: Learning the Craft of Screenwriting Through 25 of the Best and Worst Films in History. Though written for screenwriters, Pope’s work is essential to comic book writers, as well. In his introduction, Pope reflects,"[L]ife is just one damned thing after another, without apparent structure or meaning. ... Art doesn't try to imitate life, but rather distills its essence to find and reveal the truth behind the lies, the meaning behind the meaningless, the structure within the randomness" (xix).

But what if you as a writer want to emphasize that life is, in fact, “one damned thing after another,” without meaning or structure? Many writers attempt to portray what they see as the world outside their windows, with all the grim, gritty, and amoral aspects (which might prompt one to suggest that they move to a nicer neighborhood).

Even if your story focuses on the darker side of heroes, structure can keep it from spinning out of control or sputtering to a halt eight issues into a 12-issue limited series. To illustrate this point, look at the granddaddy of all “dark” super-hero comics, Watchmen.

Watchmen and Dramatic Structure

Spoiler Warning: Aspects of Watchmen are discussed below. Proceed at your own risk.

Published as a 12-issue limited series in 1986-87 and later collected into a graphic novel, Watchmen set the tone for today's grim and gritty comics. But while many fledgling writers imitated the raw violence, sex, and language of Watchmen, they failed to learn a far more valuable lesson: Watchmen makes superb use of dramatic structure.

Writer Alan Moore put his own spin on Freytag’s Pyramid. For example, the story begins with the grisly aftermath of a murder—the “hero” known as The Comedian has been thrown through a penthouse window and his blood is being washed from the sidewalk below into the gutter. The Inciting Incident—the murder—has already occurred; this means that the opening scene begins the Rising Action. (Note that the 2009 film version departs from this beginning by showing the murder at the onset.)

But what about Exposition? Moore did not neglect this vital information. Some of it is filled in by the two detectives investigating the case; other information is discovered by another “hero,” Rorschach, as he conducts his own illegal investigation. By Page 8 of the first issue, we’re well oriented to the world of Watchmen and two of its main characters. Moore successfully weaves Exposition with Rising Action while showing us only glimpses of the Inciting Incident in flashback.

Packing and Unpacking Stories

A story, as Watchmen demonstrates, does not have to begin with Exposition. The writer can start the story anywhere along Freytag’s Pyramid. However, all of the dramatic elements should be present when the story is unpacked and laid out. (If you are familiar with Watchmen, unpack the rest of it yourself and see if you can locate the other elements.)

Good writers should also unpack their own stories and see where the dramatic beats lie. This will help you avoid “lumps” or flatness in the final product, regardless of whether it lasts one issue, 12 issues, or indefinitely.

Sources:

Moore, Alan, writer, and Dave Gibbons, artist. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics, 1986.

Pope, Thomas. Good Scripts, Bad Scripts: Learning the Craft of Screenwriting Through 25 of the Best and Worst Films in History. New York: Three Rivers, 1998.